Larval stage cuticles differ from adult in the type of layers present or their relative thickness (CutFIG 6 and DCutFIG 1). The dauer cuticle is further distinguished from those of other stages in being less permeable and proportionally thicker (10.2% of the animal's cross sectional area; c.f. 4.4% for other stages) because of a reduction in body diameter and an increase in epicuticle layer thickness (Cassada and Russell, 1975; Cox et al., 1981b). See also Dauer Cuticle Chapter.

CutFIG 6: Cuticle layer organization in different larval stages.

(Red labels) Layers that are either specific to a particular stage or have distinct characteristics in that stage, relative to the adult. (Adapted from Cox et al., 1981b.)

4 Cuticle Generated By Other Tissue

The major openings of the animal are also cuticle-lined: the buccal cavity and pharynx (see Alimentary system - Pharynx), the vulva (see Reproductive system - Egg-laying Apparatus), the rectum (see Alimentary system - Rectum and Anus) and the excretory duct and pore (see Excretory system). These cuticles are secreted by underlying cells that are generally epithelial, although in the case of the buccal cavity and pharynx, other cell types may contribute (e.g. pharyngeal muscle cells). In contrast to body cuticle, cuticles that line the openings do not appear to be composed of layers. However, some contain specialized cuticular elements. The most striking examples are seen in the pharyngeal cuticle, which contains at least four different types of elements: bridging cuticle, flaps, grinder, sieve, and channels (CutFIG 7A, CutFIG 7B-E; Albertson and Thomson, 1976; Wright and Thomson, 1981). The excretory duct and pore cuticles also contain regions of distinctive patterning (CutFIG 8) These may serve to strengthen the pore and to keep it open.

CutFIG 7B-E: Ultrastructure of pharynx cuticle elements. B. Buccal cavity. (Image source: [E. Hartwieg and R. Horvitz] N2NOSE/EH5775.) C. Procorpus. D. Metacorpus (ventral is to the left). E. Terminal bulb. (Image source [MRC] JSA.)

CutFIG 8: Ultrastructure of excretory canal cuticle lining. A. TEM, longitudinal section (transverse to the pore). (Image source [Hall] N533 N1 C629B.)

B. TEM, transverse section (longitudinal to the pore). (Image source [Hall] N513B T1 1527.)

5 Cuticle Production and Molting

The first cuticle, the L1 cuticle, is laid down at the time of embryonic elongation. Contraction of circumferential actin filament bundles, which lie beneath the surface of the hypodermal apical membrane, induce elongation of the embryo and simultaneously produces ridges and furrows in the hypodermis and an overlying lipid layer called the embryonic sheath (Priess and Hirsh, 1986). This surface is thought to serve as a template for cuticle annulations (CutFIG 9A) (Costa et al., 1997). A similar contractile mechanism may be employed to pattern later stage cuticles and, possibly, the formation of alae.

CutFIG 9A: Schematic of cuticle formation and molting. L1 cuticle formation during embryonic development (longitudinal view). (Adapted from Costa et al., 1997.)

Following hatching are four post-embryonic molts whereby an entirely new cuticle is synthesized and the old cuticle is shed. The new cuticle is laid down beneath the existing cuticle, with the outer layers synthesized first and the inner layers last. Seam cells, and to a lesser extent hypodermal cells, acquire large Golgi and have vesicles containing densely staining material, consistent with the notion that high levels of protein synthesis and secretion occur at this time (Singh and Sulston, 1978). The new cuticle is initially highly convoluted and the underlying hypodermis contains folds known as plicae (CutFIG 9B).

CutFIG 9B: TEM of cuticle formation and molting. TEM, longitudinal section, of animal during a molt. (Image source: mab-5 [e1239]; him-5[e1490] [MRC] 3826-11.)

Consistent with the cyclic nature of the molting process, synthesis of cuticle components is low between molts and high prior to molts (Cox et al., 1981c). Transcriptional analysis of collagen gene activity reveals multiphasic waves of early (e.g. dpy-7), middle (sqt-1, dpy-13), and late (col-12) gene expression. It is hypothesized that collagens that are produced cotemporally may be incorporated into the same heteromeric complex or cuticle substructure (Cox et al., 1981c; Cox and Hirsh, 1985; Park and Kramer, 1994; Johnstone and Barry, 1996; McMahon et al., 2003). Some cuticle proteins are synthesized at every molt (e.g. COL-12) whereas others are stage-specific e.g., adult-specific COL-19 and BLI-1 (CutFIG 5A&B).

Molting consists of two phases: lethargus, the period of inactivity preceding cuticle shedding, and ecdysis or cuticle shedding (Singh and Sulston, 1978). In the first half of lethargus pharyngeal pumping and locomotion decrease and seam cells lose their granular appearance. Immobility is thought to result from the separation of the basal zone in the old cuticle from the underlying hypodermis. Loosening of the old cuticle begins around the head, then moves to the buccal cavity and the tail. In the second half of lethargus, the worm begins to spin and flip around its long axis. The pharynx contracts and its cuticle lining breaks; the posterior half passes into the intestine and the anterior half is expelled and shed with the body cuticle. At this time, refractile granules are apparent in the pharyngeal gland cell processes and are thought to play a role in ecdysis. As in insects, molting in C. elegans appears to be regulated by nuclear hormone receptors (Kostrouchova et al., 1998, 2001).

6 Cuticle Attachment Complexes

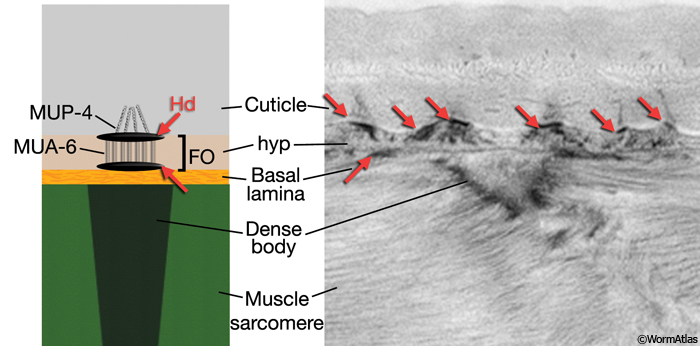

Locomotion requires the transmission of contractile force from body wall muscle to the cuticle.This force is transmitted through a series of mechanical linkages connecting body wall muscle, basal lamina, hypodermis and cuticle (CutFIG 10, CutFIG 11). The inner layer of the cuticle is attached to the apical hypodermal membrane through electron-dense attachment complexes, called hemidesmosomes, from which intermediate filaments extend into the cytoplasm. Similar complexes are also present on the basal hypodermal membrane and when apical and basal complexes are in register, a fibrous organelle (FO) is formed. Anchoring fibrils extend from FOs into the extracellular basal lamina, which is linked, in turn, to muscles through the M line and dense bodies of the sarcomere (Francis and Waterston, 1991; Hresko et al., 1994, 1999; Bercher et al., 2001; Hong et al., 2001; Hahn and Labouesse, 2001) (see also Somatic Muscle). Similar junctional complexes are also associated with non-body wall muscles (e.g. of the vulva, pharynx and rectum) and with non-muscular cells that also make tight transhypodermal contact with the cuticle such as the excretory pore, touch neuron processes, amphids and phasmids (Bercher et al., 2001).

CutFIG 11: Proteins associated with cuticle attachment complexes. Epi-fluorescent images of transgenic L3 animals (head, lateral view) expressing a reporter gene for A. mup-4 (strain source B. Bucher) and B. intermediate filament gene mua-6 (strain source V. Hapiak and J. Plenefisch).

7 Cuticle Mutants

Proper cuticle formation and function is regulated by a number of different genes, many of which are mentioned above and have been described in detail previously (for review see Page and Johnstone, 2007 in WormBook). When cuticle formation is altered, this can lead the changes in the appearance of the animal, producing phynotypes such as long or dumpy (CutFIG 12). Addtionally, animals can exhibit defects in the surface as seen in the structure of their annuli, furrows and alae (CutFIG 12 & CutFIG 13). These altered cuticle structures can also result in molting and movement defects (CutFIG 13).

CutFIG 12: Cuticle structure of mutant animals. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) images show annuli and furrow structures of worm cuticle (NanoWizzard3, JPK). Worms were immobilized, immersed in M9 buffer and imaged live using a NanoWizard3 (JPK). A-D. Topography images of 9µm of cuticle. E-H. 3D overlay of topgraphy and elastic modulus from A-E. A&E. Cuticle from a wildtype N2 animal. B&F. Cuticle from a lon-2 animal showing a greater distance between annuli. Mutants are longer than wildtype. C&G. Cuticle from a dpy-5 animal showing a shorter period between annuli. Mutants have a dumpy phenotype that is shorter than wildtype. D&H. Cuticle from a dpy-7animal showing a disorganized cuticle structure. These mutants are dumpy and have no annuli present. (AFM image source C. Essmann, Essmann et al., 2017.)

CutFIG 13: Cuticle defects in an eff-1 mutant. Four scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of adult eff-1 mutants reveal a variety of defects in the cuticle. The EFF-1 protein is required for proper cell-cell fusion events in many syncytial tissues, including hypodermis, seam cells and vulval epithelium (cf. Shemer et al., 2004; Gattegno et al., 2007). A. Molting defects are fairly common ineff-1 animals as indicated by image showing adult head still retaining the L4 cuticle, attached to the opening of the buccal cavity (black arrowhead).

B. Vulva is partially extruded (white arrowhead) and the alae are often split into two parallel rows (black arrows) due to defects in the underlying seam cells, which often fail to fuse into a single row during late larval development. C. Alae in the tail are again discontinuous (black arrow), reflecting a highly irregular positioning of the underlying seam cells.

D. Adult tail still retains the L4 cuticle (black arrowhead) due to defective molting. (Image source:

Hall archive; sample preparation and imaging by Carolyn Marks and David Hall.)

8 References

Albertson, D.G. and Thomson, J.N. 1976. The pharynx of Caenorhabditis elegans. Phil. Trans. Royal Soc. London 275B: 299-325. Article

Bercher, M., Wahl, J., Vogel, B.E., Lu, C., Hedgecock, E.M., Hall, D.H. and Plenefisch, J.D. 2001. mua-3, a gene required for mechanical tissue integrity in Caenorhabditis elegans, encodes a novel transmembrane protein of epithelial attachment complexes. J. Cell Biol. 154: 415-426. Article

Bird, A.F. and Bird, J. 1991. The Exoskeleton. In The structure of nematodes. (ed. A.F. Bird and J. Bird). chap. 3, pp. 44-74. Academic Press, San Diego.

Blaxter, M.L. and Robertson W.M. 1998. The Cuticle. In The Physiology and Biochemistry of Free-living and Plant-parasitic Nematodes, (ed. R.N. Perry and D.J. Wright) pp. 25-48. CAB International, New York. Abstract

Brenner, S. 1974. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77: 71-94. Article

Cassada, R.C. and Russell, R.L. 1975. The dauer larva, a post-embryonic developmental variant of the nematode C. elegans. Dev. Biol. 46: 326-342. Abstract

Chitwood, B.G. and Chitwood, M.B. 1950. An introduction to nematology. University Park Press, Baltimore.

Costa, M., Draper, B.W. and Priess, J.R. 1997. The role of actin filaments in patterning the Caenorhabditis elegans cuticle. Dev. Biol. 184: 373-384. Article

Cox, G.N. and Hirsh, D. 1985. Stage-specific patterns of collagen gene expression during development of Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 5: 363-372. Article

Cox G.N., Kusch M. and Edgar R.S. 1981a. Cuticle of C. elegans: Its isolation and partial characterization. J. Cell Biol. 90: 7-17. Article

Cox, G.N., Staprans, S. and Edgar, R.S. 1981b. The cuticle of C. elegans. II. Stage-specific changes in ultrastructure and protein composition during postembryonic development. Dev. Biol. 86: 456-470. Abstract

Cox, G.N., Kusch, M., DeNevi, K. and Edgar, R.S. 1981c. Temporal regulation of cuticle synthesis during development of C. elegans. Dev. Biol. 84: 277-285. Abstract

Essmann, C.L., Elmi, M., Shaw, M., Anand, G.M., Pawar, V.M. and Srinivasan, M.A. 2017. In-vivo high resolution AFM topographic imaging of Caenorhabditis

elegans reveals previously unreported surface structures of

cuticle mutants. Nanomedicine 13: 183-89. 10.1016/j.nano.2016.09.006 Abstract

Francis, R. and Waterston, R.H. 1991. Muscle cell attachment in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Cell Biol. 114: 465-479. Article

Gattegno, T., Mittal, A., Valansi, C., Nguyen, K.C.Q., Hall, D.H., Chernomordik, L.V. and Podbilewica, B. 2007. Genetic control of fusion pore expansion in the epidermis of Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Biol. Cell 18: 1153-66. Article

Hahn, B.S. and Labouesse, M. 2001. Tissue integrity: hemidesmosomes and resistance to stress. Curr. Biol. 11: R858-R861. Article

Herndon, L.A., Schmeissner, P.J., Dudaronek, J.M., Brown, P.A., Listner, K.M., Sakano, Y., Paupard, M.C., Hall, D.H. and Driscoll, M. 2002. Stochastic and genetic factors influence tissue-specific decline in ageing C. elegans. Nature 419: 808-814. Abstract

Higgins, B.J. and Hirsh, D. 1977. Roller mutants of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Gen. Genet. 150: 63-72. Abstract

Hong, L., Elbl, T., Ward, J., Franzini-Armstrong, C., Rybicka, K.K., Gatewood, B.K., Baillie, D.L. and Bucher, E.A. 2001. MUP-4 is a novel transmembrane protein with functions in epithelial cell adhesion in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Cell Biol. 154: 403-414. Article

Hresko, M.C., Williams, B.D. and Waterston, R.H. 1994. Assembly of body wall muscle and muscle cell attachment structures in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Cell. Biol. 124: 491-506. Article

Hresko, M.C., Schriefer, L.A., Shrimankar, P. and Waterston, R.H. 1999. Myotactin, a novel hypodermal protein involved in muscle-cell adhesion in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Cell Biol. 146: 659-672. Article

Johnstone, I.L. and Barry, J.D. 1996. Temporal reiteration of a precise gene expression pattern during nematode development. EMBO J. 15: 3633-3369. Article

Jones, S.J.M. and Baillie, D.L. 1995. Characterization of the let-653 gene in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Gen. Genet. 248: 719-726. Abstract

Kostrouchova, M., Krause, M., Kostrouch, Z. and Rall, J.E. 1998. CHR3: A Caenorhabditis elegans orphan nuclear hormone receptor required for proper epidermal development and molting. Development 125: 1617-1626. Article

Kostrouchova, M., Krause, M., Kostrouch, Z., and Rall, J.E. 2001. Nuclear hormone receptor CHR3 is a critical regulator of all four larval molts of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98: 7360-7365. Article

Kramer, J.M. and Johnson, J.J. 1993. Analysis of mutations in the sqt-1 and rol-6 collagen genes of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 135: 1035-1045. Article

Kramer, J.M. 1997. Extracellular Matrix. In C. elegans II (ed. D.L. Riddle et al.) pp. 471-500. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, New York. Article

Kusch M. and Edgar, R.S. 1986. Genetic studies of unusual loci that affect body shape of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans and may code for cuticle structural proteins. Genetics 113: 621-639. Article

Lewis, E., Sebastiano, M., Nola, M., Zei, F., Lassandro, F., Ristoratore, F., Cermola, M., Favre, R. and Bazzicalupo, P. 1994. Cuticulin genes of nematodes. Parasite 1: 57-58. Abstract

Link, C.D, Silverman, M.A, Breen, M., Watt, K.E., and Dames, S.A. 1992. Characterization of Caenorhabditis elegans lectin-binding mutants. Genetics 131: 867-881. Article

Liu, Z., Kirch, S. and Ambros, V. 1995. The Caenorhabditis elegans heterochronic gene pathway controls stage-specific transcription of collagen genes. Development 121: 2471-2478. Article

McMahon, L., Muriel, J.M., Roberts, B., Quinn, M. and Johnstone, I.L. 2003. Two sets of interacting collagens form functionally distinct substructures within a Caenorhabditis elegans extracellular matrix. Mol. Biol. Cell. 14: 1366-1378. Article

Nelson, F.K., Albert, P.S. and Riddle, D.L. 1983. Fine structure of the Caenorhabditis elegans secretory-excretory system. J Ultrastruct. Res. 82: 156-171. Article

Nicholas, H. and Hodgkin, J. 2004. The ERK MAP kinase cascade mediates tail swelling and a protective response to rectal infection in C. elegans. Curr. Biol. 14: 1256-1261. Article

Page, A.P. and Johnstone, I.L. 2007. The Cuticle. In WormBook (ed. The C. elegans Research Community, WormBook, doi/10.1895/wormbook.1.138.1. Article

Park, Y-S. and Kramer, J.M. 1994. The C. elegans sqt-1 and rol-6 collagen genes are coordinately expressed during development, but not at all stages that display mutant phenotypes. Dev. Biol. 163: 112-124. Abstract

Politz, S.M., Philipp M., Estevez M., O'Brien P.J. and Chin K.J. 1990. Genes that can be mutated to unmask hidden antigenic determinants in the cuticle of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 87: 2901-2905. Article

Priess, J.R. and Hirsh, D.I. 1986. C. elegans morphogenesis: The role of the cytoskeleton in elongation of the embryo. Dev. Biol. 117: 156-173. Abstract

Sebastiano, M., Lassandro, F. and Bazzicalupo, P. 1991. cut-1 a Caenorhabditis elegans gene coding for a dauer-specific noncollagenous component of the cuticle. Dev. Biol. 146: 519-530. Abstract

Shemer, G., Suissa, M., Kolotuev, I., Nguyen, K.C., Hall, D.H. and Podblilewicz, B. 2004. EFF-1 is sufficient to initiate and execute tissue-specific cell fusion in C. elegans. Curr. Biol. 14: 1587-91. Article

Singh, R.N. and Sulston, J.E. 1978. Some observations on moulting in C. elegans. Nematologica 24: 63-71. Abstract

Thein, M.C., McCormack, G., Winter, A.D., Johnstone, I.L., Shoemaker, C.B. and Page, A.P. 2003. Caenorhabditis elegans exoskeleton collagen COL-19: an adult-specific marker for collagen modification and assembly, and the analysis of organismal morphology. Dev. Dyn. 226: 523-539. Article

Wright, K.A. and Thomson, J.N. 1981. The buccal capsule of Caenorhabditis elegans (Nematoda: Rhabditoidea): An ultrastructural study. Can. J. Zool. 59: 1952-1961. Article

|